Looking Like the Enemy

Asian Americans of the Vietnam War

This virtual exhibit honors the Asian American perspective and experiences during the Vietnam War. Instead of focusing on combat, we focus on the stories that Asian Americans tell on the front lines and the home front.

Research question:

How did a common identity in race with “America’s enemy” affect not only how Asian American perceived themselves, but how fellow soldiers, countrymen, and political leaders perceived them? How did this affect response to the war?

Out of the 8.7 million Americans reported to have served in the Vietnam War, over 88,000 identified as Asian Pacific American in the 1990 Census.

The Vietnam War was also the first war where Asian Americans were not separated into separate military units by race, but alongside non-Asian soldiers. Asian American organizations on the home front also emerged to speak out against the war and what it stood for.

This exhibit investigates how Asian American identity affected both soldiers and citizens in political identity, combat experience, and organization.

What was the Vietnam War to Americans?

What did Asian American soldiers in the Vietnam War go through?

What made Asian American protests of the war unique?

Vietnam, America, and the Cold War

The Vietnam War rests in the greater context of the Cold War, a global conflict between the Soviet Union (present-day Russian Federation and former states) and the United States of America. Coming hot off the heels of World War II, the Soviet Union was beginning to make its way to butt heads with the United States in not just ideologies, but military and economic might as Soviet influence made its way into Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia. This made American politicians and strategists consider the Soviet Union a threat to capitalist interests and empire.

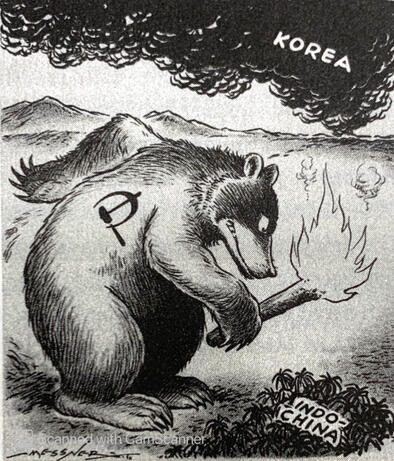

Korea and Vietnam. Political Cartoon, Rochester Times-Union, September 25, 1950

Though both countries saw no armed conflict within their own borders during these decades, skirmishes and wars were instead played out across multiple fronts called "buffer states" as defense against communism encroaching on free states by the Soviet Union. In retaliation, the Soviet Union began to train troops in their own buffer states with their own weapons. All the while, both superpowers built a stockpile of nuclear armaments as a deterrent from a true war breaking out against the Soviet Union and the United States. This arms race continued well into the late 20th century.

One of the hotbeds of the Cold War's conflict with buffer states was Southeast Asia, where both nations' spheres of influence were right next to each other and at constant contention. Though the United States told the public that they were stationing troops and arms in counties like Laos, Vietnam, and the Philippines to prevent the spread of communism, in reality, the United States' presence overseas in Southeast Asia was no better than the Soviet Union's. They were imposing imperialistic policies and linguistic, class, social, and racial barriers upon the native population.

This war of ideologies between the two global superpowers had real, harmful effects on those who fought for what they were told was the right side. Citizens of buffer states caught between the USSR and the United States could do nothing but be thrust into the terror of war on their homes from both sides.

Other than being forced into the war by the draft, many Americans enlisted or volunteered in the war effort as an effect of American propaganda and media that painted communism as a threat to not just the world, but the United States. It was not until these soldiers were actually on the battlefield and facing the Cold War with their lives on the line that they saw the truth of what they were told in recruitment.

A Working Class War

Those who were drafted into the United States military were teenage and adult men ages 19 and up. The draft was avoidable by men from rich families which resulted in around 80% of America's Vietnam troops were working-class or poor income soldiers. This has caused many historians to coin the Vietnam War as "a working-class war." These teenagers and working-class men enlisted with the mindset that they would be contributing to the United States in a better way than they had in menial jobs with low pay; instead of doing what was considered "dirty work" by their economically-stratified society, they could find reward in their sacrifice in Vietnam.

Thus, soldiers who were seeking purpose in their lives, forced into dire circumstances due to the institutional structures that prevented them from escaping class and social struggle, instead found themselves battling a foreign enemy on behalf of the upper class. As war dragged on and millions perished from their injuries, being killed in action (KIA), or are still missing today as prisoners of war (POW), the harsh reality of the Vietnam War and what it was to the common American was means to an end for politicians who wanted to expand capitalism's empire the next continent over.

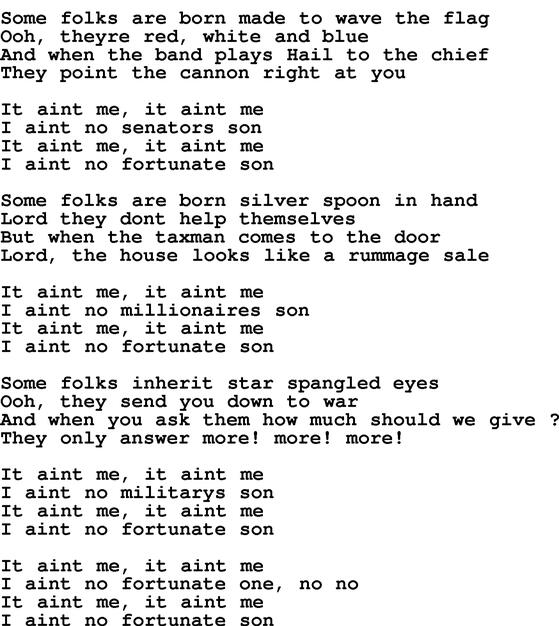

Fortunate Son (right) is an iconic protest song from the Vietnam War era that highlights the class divide of the war. To the greater working-class population of the United States, rhetoric that centered around this class divide was a unifying factor for both the GIs overseas and the protesting citizens at home.

Fortunate Son (lyrics). Clarence Clearwater Revival, October 1969.

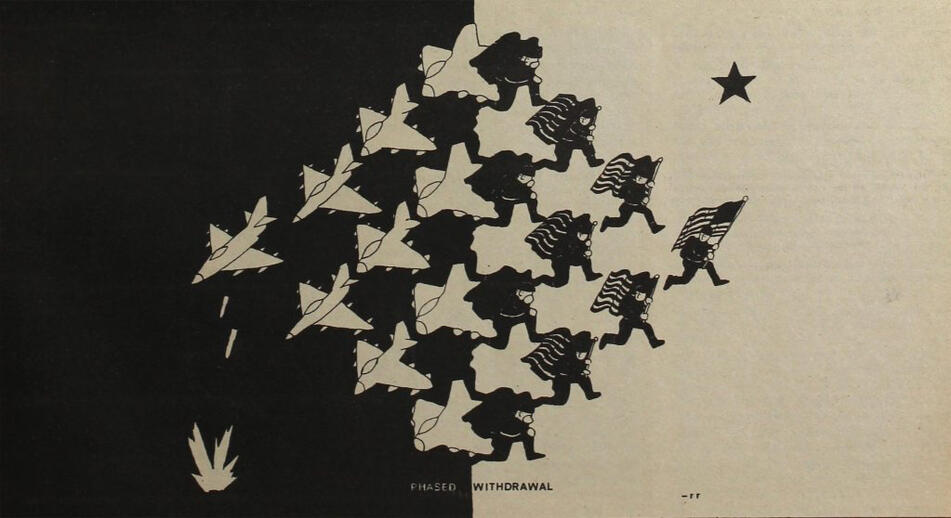

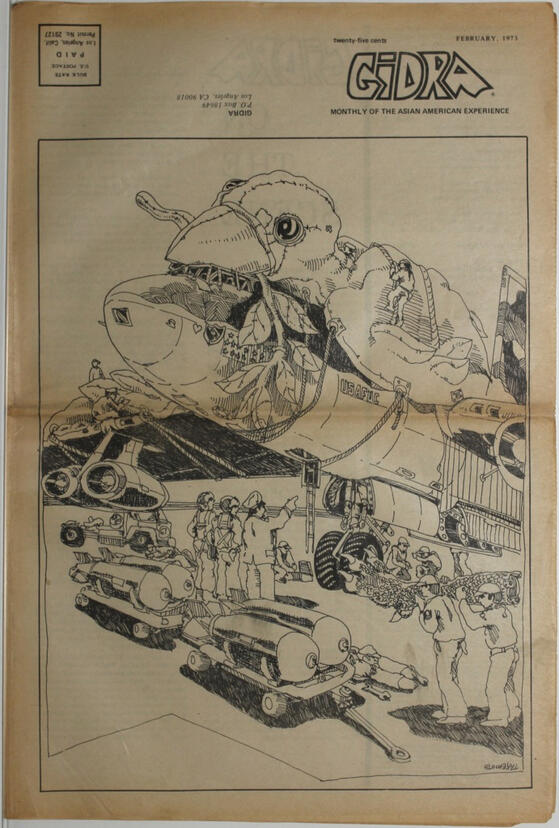

Phased Withdrawal, Courtesy of the Gidra Collection. January, 1973

Though focusing on the class struggle that the Vietnam War represented in the United States, keeping the spotlight on such a broad idea erases the history that Asian Americans in particular have with the Vietnam War. Indeed, many Asian Americans who were drafted into the ranks were also poor like their non-Asian comrades, but their race played a specific part into how they were treated from boot camp to the front lines.

In other sections of this exhibit, you can explore how "looking like the enemy" alienated Asian American GIs among their ranks despite the prevailing idea that in combat, all soldiers are equal. Reflect on the context of the Vietnam War being a "working-class war" and how that connects to material we have discussed in class. Recall how Asian migrant workers were used as strikebreakers on the east coast United States during strikes, driving wedges between class and race. Think about the underlying agendas an institution that benefits from oppressing its citizens may have in sending its citizens to a war of ideologies. How could this shape the way we look back at these points in history and the people who lived it?

The Front Lines

It was continual harassment, anything from 'dinks,' 'slant eyes,' 'rice bowl,' to threats of being shot in the back...It was like fighting two wars.

— Lance Luke, Vietnam veteran

Asian Americans were enlisted in all parts of military service, from active combat to medical posts, to intelligence and clerical work. Despite their strong presence in the war, many were victim to anti-Asian racism, the same that was used to dehumanize the native Vietnamese population they were fighting against.

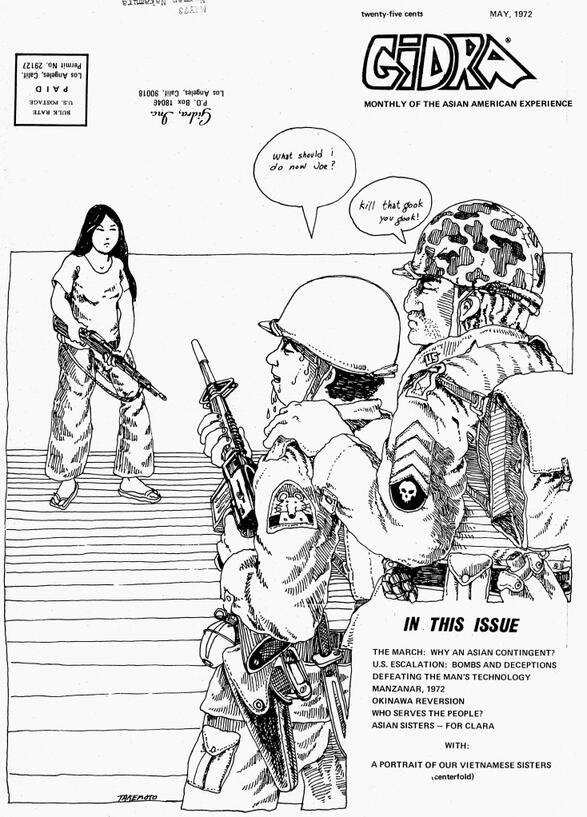

The slur "gook" has a prolific spot in the history of the Vietnam War and refers to Southeast Asians. This slur was commonly used to also refer to Asian American servicemen, implying the notion that the concept of an "Asian" person was monolithic; their true heritage did not matter, just that they looked Asian enough to be called a "gook." It was used to strip the identities of soldiers who were already referred to on a surname basis instead of first names, especially in basic training and boot camp, the entry point for GIs. "Gook" was used to group Asian Americans in with the enemy; no matter their reason for enlisting in the United States military, they would still be considered traitors, spies, and the enemy nonetheless.

In the future, this creation of the pan-Asian identity out of racist circumstance became a cornerstone in modern Asian American theory and identity. However, in the context of the Vietnam War, it would be an attack on the patriotism and sacrifices Asian Americans made for the United States' cause.

One day, right in the middle of the class, a drill sergeant comes marching into one of the classes and yells out, ‘Private Nakayama, stand up'... he says ‘alright everyone, this is what a gook looks like.’

— Mike Nakayama, Vietnam veteran

The monolithic perception of Asian Americans put them at particular risk of being mistaken for enemy combatants, whether on purpose or as a result of militaristic physical and mental tolls soldiers were put through in training and combat. Asian American women additionally experienced sexism and racism like their male counterparts, being mistaken not only for the "enemy," but sex workers and spoke about sexual assault and misogynistic abuse directed at them in military units, infirmaries, and daily life in American bases.

Anti-Asian racism is at the core of the Vietnam War, and it is impossible to deny that the very combatants that were on America's side were also victim to the same racism used to indoctrinate them into dehumanizing the Vietnamese population. As many Asian American veterans put it, this was a conflict that they had to face every day as a soldier or a support unit. Their lives were constantly on the line even behind what other GIs would consider "safe" due to their appearance; if they were not being harassed with slurs like "gook," they were being physically assaulted by fellow countrymen who considered them the enemy.

In short, the sacrifices of Asian American lives could have been in vain because they were not recognized as truly American like a non-Asian GI. Were it not for historians recording the experiences of those who are able to share them, this critical point of discussions around the Vietnam War falls into the cycle of erasure and misrepresentation.

It really hurt inside that I had just spent 12 hours treating their buddies, and they thought I was just some Vietnamese whore.

— Lily Jean Lee Adams, Combat nurse (12th Evac. Hospital, Vietnam)

Political Cartoon, Courtesy of the Gidra Collection. Vol. IV, No. 5 (May 1972)

Long before I'm coming into the perimeter, I was yelling so I wouldn't be mistaken for the enemy. Basically, it put me in a position that it's easy to get killed.

— Lorenzo Silvestre, Vietnam veteran (USMC)

As you read the oral histories and quotes from Asian American Vietnam GIs in this section, consider the context that has been presented to you. Ask yourself:

What consequences does treating Asian Americans as a singular, pan-Asian monolith have on the perception of Asian American soldiers?How might the dehumanization of Vietnamese civilians and enemy combatants affect how non-Asian soldiers saw their Asian American comrades?What points would Asian American protesters on the home front emphasize in their demonstrations?Could Asian American veterans experience certain symptoms of post-traumatic stress when they return to the United States?

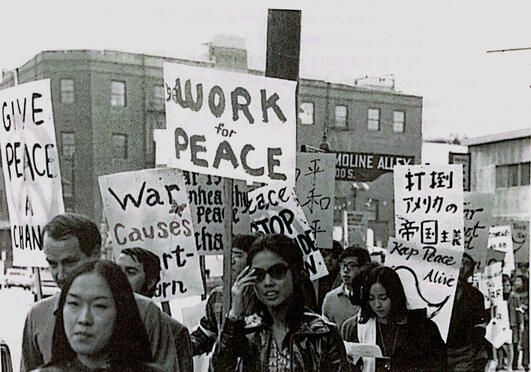

The Vietnam War was a turning point for the United States as its coverage in media on the home front and accounts from veterans and combatants on the field sparked protests across the nation against the horrors of war. In particular, the battleground of Southeast Asia and specifically Vietnam rallied Asian Americans on the home front to protest. Their unique position in looking like America's "enemy" was not unfamiliar territory, given World War II just decades prior. Asian Americans were used to being mistaken as adversaries, even if they were American citizens. This time around, Asian American political identity and organization had evolved since then, and Asian Americans were prepared and ready to stand with other groups in speaking out in opposition to the Vietnam War.

In the same decade, the term "Asian American" was coined as a pan-Asian, politically-rooted identity for Asian Americans to organize and rally under. One prolific publication at the roots of Asian American activism was Gidra, a serial publication based in Los Angeles. Multiple authors and artists contributed political cartoons, commentary, essays, columns, and more to bring visibility to the unique perspective of Asian Americans that went underrepresented in mainstream media, and this included the experiences of Asian American GIs in the Vietnam War.

Some Gidra political cartoons have already been featured in this exhibit. One of the first articles regarding xenophobia and anti-Asian racism was in fact the experiences of a Vietnam War soldier and what he saw on the front lines. Due to its unique birth during the 1960s and simultaneous run during the Vietnam War, Gidra is an archive into Asian American political commentary and organization on the stateside.

Political Cartoon, Courtesy of the Gidra Collection. Vol. V, No. 2 (February 1973)

With the birth of the Asian American political identity came widespread Asian American activism. In particular, opposition to the Vietnam War was a primary platform for pan-Asian organization across multiple demographics; older Asian Americans were direct victims to the concentration camps of Japanese Americans in World War II, Asian American students rallied on campuses for their fellow drafted students, and Asian American women brought awareness to sexual violence against Asian women overseas as a result of American imperialism in Southeast Asia. This unique perspective of Asian America made Asian American protests against the Vietnam War unique: the war was a symbol of the violence Asians and Asian Americans experienced.

Though Asian American organization was nationwide and spread out thin, the diversity within the pan-Asian identity in language, age, geography, and class was critical to demonstrations and political activism. Another key point Asian Americans were up against during this time was the myth of the "model minority," as white liberals in particular ignored the anti-racist platform and BIPOC solidarity the Asian American movement emphasized.

Asian American protest of the Vietnam War in

Los Angeles. Late 1960s

Courtesy of the Gidra Collection.

It was no accident that Asian America was born at the peak of the Vietnam War.

— Karen L. Ishizuka, historian

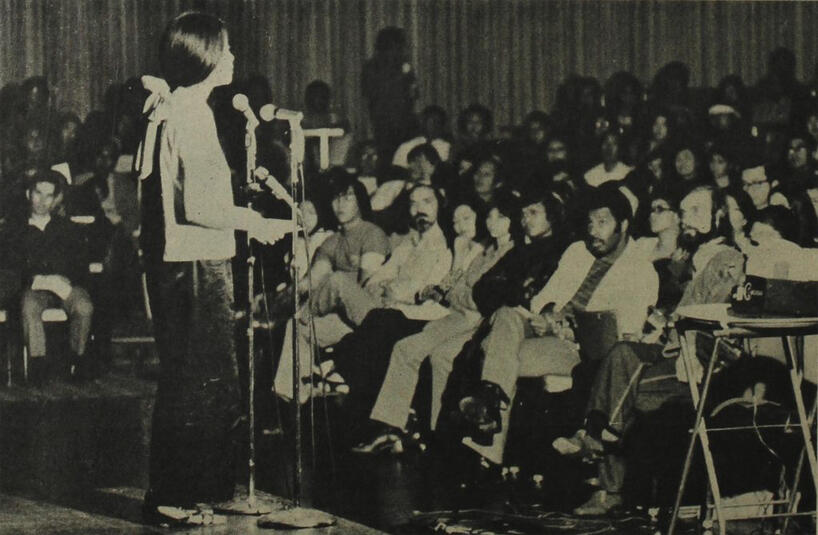

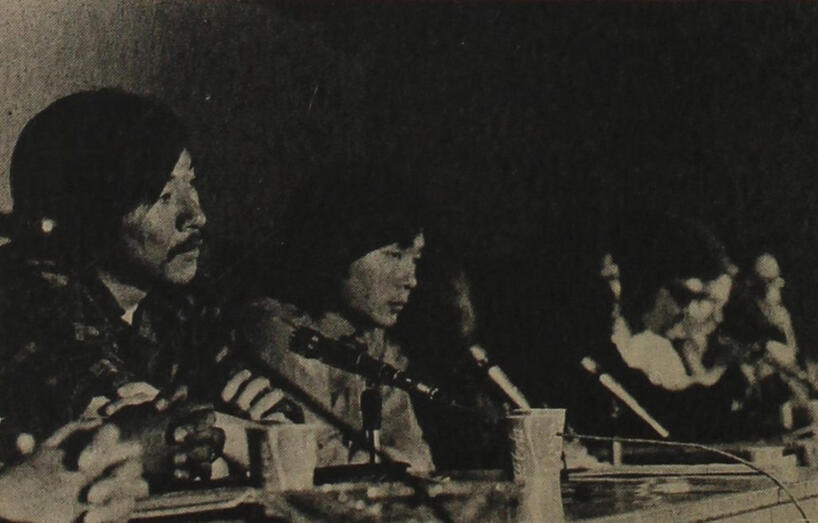

Community organizer Pat Sumi speaks about her experience in Southeast Asia at a Peace Sunday event in Los Angeles. May 16, 1971. Courtesy of the Gidra Collection.

Asian American veterans were also notable participants in the anti-war movement on the home front. They had experienced the violence of not just war, but their fellow soldiers and superiors firsthand and were prepared to recall the abuse they experienced while on tour. The quotes mentioned in the front lines section of this exhibit were only few of many from GIs who testified in investigations of the United States military and during demonstrations, showing that even people sacrificing their lives for their nation were not spared from anti-Asian racism.

The complicated identity of being both a victim and working cog in American imperialism was not lost to Asian Americans. There was a sense of connection to the native Vietnamese population that they were demonstrating for, but also actively killing in the name of U.S. expansion into Southeast Asia. Asian American demonstrations emphasized this difficult position in the acknowledgement of their privilege as first-world country citizens.

However, it was not necessarily enough to absolve Asian American veterans of the Vietnam war nor Asian American citizens of the concrete actions of their county. Thus, they persisted in active demonstrations and the creation of protest media for the end of the Vietnam War and what it stood for: American imperialism and its violence.

Nick Nakatani and Mike Nakayama testify at the Winter Soldier Investigation, an event sponsored by Vietnam Veterans Against the War to publicize war crimes committed by the U.S. military in Vietnam. Courtesy of the Gidra Collection.

References

Thank you for visiting our online exhibit. This website was created in collaboration between Nara Chai and Heqing Zhao for ETHN 163J, a course at the University of California, San Diego.

On this page, you will find the references and sources for documents featured in this exhibit plus further reading. We strongly encourage those who are interested in the history of Asian Americans and the Vietnam War to do their own research and pursue the sources listed.

A., D. R. C., Mochizuki, K., & Wong, D. (1999). Southeast Asia: Looking Like the Enemy. In A Different Battle: Stories of Asian Pacific American Veterans (pp. 22–24). essay, University of Washington Press/Wing Luke Asian Museum.

Appy, C. G. (2003). A Working Class War. In R. J. McMahon (Ed.), Major Problems in the History of the Vietnam War (3rd ed., pp. 250–260). essay, Houghton Mifflin Company.

Dang, J. (1998, December 3-9). The Wounds of War-And Racism. AsianWeek.

Densho. (n.d.). Gidra Collection. Densho Digital Repository. Retrieved March 7, 2022, from https://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-297/

Dizon, L. (1994, January 16). Expatriates Vent Anger at Author, Movie Portrayals. Los Angeles Times.

Hughes, M. (2020, May 11). THOUGHTS ON PBS' 'ASIAN AMERICANS' FROM THOSE WHO LIVED IT. Retrieved from http://www.tvworthwatching.com/post/Thoughts-on-PBS-Asian-Americans-From-Those-Who-Lived-It.aspx.

Ishizuka, K. L. (2019, May 7). Looking Like the Enemy: Political Identity & the Vietnam War. Pacific Council on International Policy. Retrieved from https://www.pacificcouncil.org/newsroom/looking-enemy-political-identity-vietnam-war

Lawrence, M. A. (Ed.). (2014). The Vietnam War: An International History in Documents. Oxford University Press.

Wallace, N. (2017, November 15). In the Belly of the Monster: Asian American Opposition to the Vietnam War. Densho. Retrieved from https://densho.org/catalyst/asian-american-opposition-vietnam-war/